Ray M Merrill

Brigham Young University, USA

Title: Conditional survival among female breast cancer patients in the United States

Biography

Biography: Ray M Merrill

Abstract

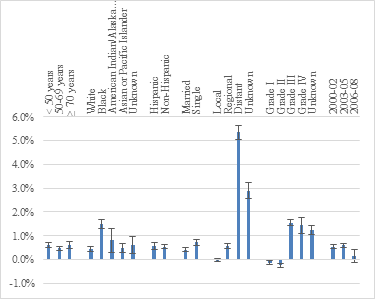

The relative cancer survival rate may be more meaningful to patients because it indicates the chance they will not die from the specific disease. This measure can be further tailored to patients by updating it according to time already survived and for selected personal characteristics. In the current study, conditional relative survival for female breast cancer is presented, based on cases diagnosed during 2000-2008 and followed up through 2013, using population-based data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute. Five-year relative survival improved from 89% at diagnosis to 93% (4.9%) for patients who had already survived 5 years. Five-year relative survival was 98% for local disease, 85% regional disease, and 30% for distant disease; 100% for Grade I, 94% for Grade II, 81% for Grade III, and 80% for Grace IV; 90% for Whites, 78% for Blacks, 82% for American Indians/Alaska Natives, and 91% for Asians; and 93% for married and 85% for singles. Improvement in 5-year relative survival from diagnosis to five years already survived was -1.1% for local disease, 3.2% regional disease, and 91.4% for distant disease; -0.9% for Grade I, -0.7% for Grade II, 11.4% for Grade III, and 14.2% for Grace IV; 3.9% for Whites, 13.4% for Blacks, 8.8% for American Indians/Alaska Natives, and 3.5% for Asians; and 2.8% for married and 6.8% for singles. Age and ethnicity had little influence on conditional relative survival. The association between 5-year relative survival and time already survived within stage groups remains similar after adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, marital status, and tumour grade.

Recent Publications

1. Merrill RM, Hunter BD. Conditional survival among cancer patients in the United States. Oncologist 2010;15(8):873-82.

2. Hieke S, Kleber M, Konig C, et al. Conditional survival: A useful concept to provide information on how prognosis evolves over time. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21(7):1530-6.

3. Tao L, Gomez SL, Keegan TH, et al. Breast Cancer Mortality in African-American and Non-Hispanic White Women by Molecular Subtype and Stage at Diagnosis: A Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24(7):1039-45.

4. Chen L, Li CI. Racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by hormone receptor and HER2 status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24(11):1666-72.

5. Baquet CR, Mishra SI, Commiskey P, et al. Breast cancer epidemiology in blacks and whites: disparities in incidence, mortality, survival rates and histology. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(5):480-88.

6. Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, et al. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA 2015;313(2):165-73.

7. Brandt J, Garne JP, Tengrup I, et al. Age at diagnosis in relation to survival following breast cancer: a cohort study. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:33.

8. Doty MM, Beutel S, Rasmussen PW, et al. Latinos have made coverage gains but millions are still uninsured. The Commonwealth Fund Blog, April 27, 2015.

9. Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3869-76.

10. Gomez SL, Hurley S, Canchola AJ, et al. Effects of marital status and economic resources on survival after cancer: A population-based study. Cancer 2016;122:1618-25.

11. Sammon JD, Morgan M, Djahangirian O, et al. Marital status: a gender-independent risk factor for poorer survival after radical cystectomy. BJU Int 2012;110(9):1201-9.

12. Zhang J, Gan L, Wu Z, et al. The influence of marital status on the stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival of adult patients with gastric cancer: a population-based study. Oncotarget 2016; Epub ahead of print.